The New USPSTF Recommendation: Prevention of Maternal Depression

By Joy Burkhard, MBA

Founder, 2020 Mom

We had the opportunity to pull leaders in the field together to review the draft USPSTF recommendation. To learn what was discussed read more here.

It has now become more well known that maternal mental health disorders are the most common complication of pregnancy and childbirth.

In 2017, after the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) overturned its position to recommend screening for maternal depression, the United States Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) changed its position to now recommend maternal depression screening.

Now, in 2019, the USPSTF released one of the firsts of its kind, a recommendation for a clinical intervention to prevent a potential disorder, not just screen for it retrospectively. The disorder? Maternal depression. The recommendation was published in on the USPSTF website and in the Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) Network.

What is the USPSTF?

It’s important to note what the USPSTF (“The Task Force”) is and why the recommendations of its clinicians matters. The Task Force is an independent panel of experts in primary care that reviews evidence to develop recommendations for clinical screening and preventive services. The 2010 Affordable Care Act requires insurers to cover at no cost to patients, recommendations with substantial or moderate (A or B respectively) net benefit.

What the Task Force Found (and didn’t find):

The Task Force found convincing evidence (grade B) that counseling interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT), are effective in preventing perinatal depression.

Interestingly, they didn’t issue a recommendation to provide the following preventive interventions (suggesting there either wasn’t enough evidence or the evidence didn’t support these interventions): Physical activity, education, supportive interventions, and other behavioral interventions, such as infant sleep training and expressive writing. Pharmacological approaches, including the use of nortriptyline, sertraline, and omega-3 fatty acids, were also not recommended (as either A or B) interventions to prevent maternal depression.

Only counseling demonstrated enough scientific evidence of preventive benefit. The report calls for health providers to seek out women with certain risk factors and guide them to the types of counseling programs that can be effective in preventing depression.

How Do Providers Identify Who Should Receive Preventive Counseling?

According to the Task Force, “clinical risk factors that may be associated with development of perinatal depression” include:

Personal or family history of depression

History of sexual abuse

Unplanned/unwanted pregnancy

Current stressful life events (housing move, job change, key change in relationship status, etc.)

Diabetes or gestational diabetes

Complications during pregnancy (premature contractions, hyperemesis)

Low income

Lack of family/social support

Teen parent

Single parent

The Task Force also goes on to note “There are limited data on the best way to identify women at increased risk for perinatal depression...A pragmatic approach would be to provide counseling interventions to women with one or more of the following:

Personal history of depression

Current depression symptoms that do not reach diagnostic threshold

-or-

Low income, young, or single parenthood

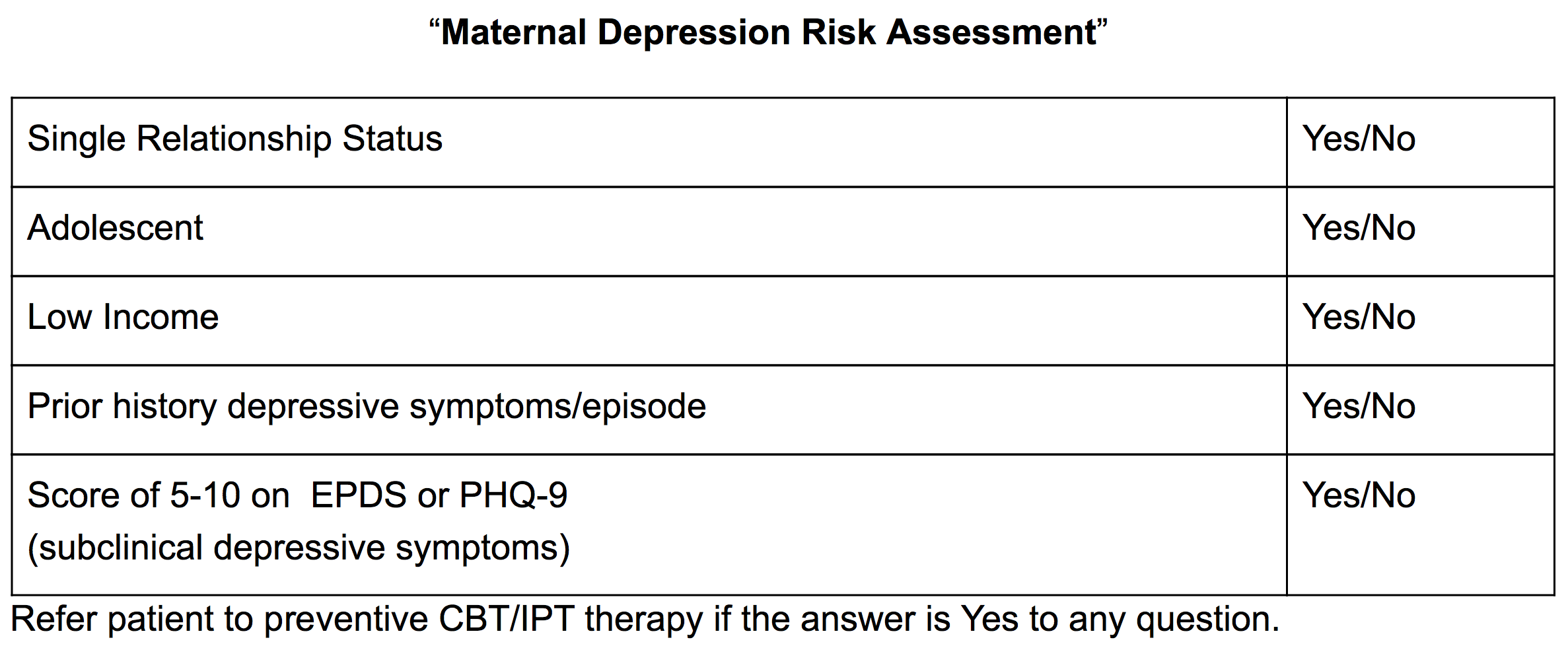

With that in mind, a tool like the following, could be used to identify risk and be aptly named “Maternal Depression Risk Assessment.”

Will This Make an Immediate Difference?

The kicker as usual is that a woman is still at the mercy of her primary care provider (which includes her obstetric provider) to be screened/referred. There is no federal requirement that PCPs/obstetricans actually provide recommended screenings. As most women who are suffering from maternal mental health (MMH) disorders aren’t being screened by their PCPs/obstetricians, it’s also unlikely this recommendation will have any short term effect outside of progressive health systems.

We Have Learned That This Never Happens Overnight. So What Does it Take?

First and foremost, we must build up treatment which starts with adequate insurance reimbursement to mental health providers and adequate reimbursement for PCP/obstetric providers who deliver brief CBT / IPT. Workforce development incentives are also necessary to recruit new clinicians into the field in order to address mental health shortages.

Second, even with referral pathways, PCPs and obstetricians are very busy and adding routine screening of patients could take a decade or more without active pressure to adopt the guidelines (AHRQ).

Things like the following will help:

Practices modifying electronic medical record questions prompting the provider to assess risk;

Insurers reimbursing for and measuring screening (on a fee for service basis vs. a flat rate “global capitation” for all maternity care);

Employers/state medicaid agencies asking insurers to create and report on MMH quality improvement programs and case management/care coordination programs.

There is much work to do, but we will get there.

2020 Mom is committed to working with stakeholders and advocates and won’t stop until there is evidence the entire U.S. healthcare system has prioritized this work.