CMS’ Toolkit on Postpartum Care Addresses Postpartum Depression – But Misses a Critical Opportunity to Address OB Payment and Peer Support

By Joy Burkhard, MBA, and Sarah Johanek, MPH

In August 2023, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Service (CMS) published a postpartum toolkit for State Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Agencies titled Increasing Access, Quality, and Equity in Postpartum Care in Medicaid and CHIP. The toolkit addresses postpartum depression; however, we point out opportunities CMS missed, including addressing the role of the obstetric provider and peer support.

According to CMS, the toolkit is “intended to support Medicaid and CHIP programs in their efforts to improve the delivery of postpartum care to reduce rates of morbidity, mortality, and disparities.” It was created through an environmental scan to find strategies that are effective in increasing postpartum care visits and improving the quality of postpartum care specific to Medicaid and CHIP populations.

Our work shaping and reporting on national mental health policy is made possible through a 2020-2024 capacity grant from the Perigee Fund.

The toolkit outlines the following specific to Maternal Mental Health:

The toolkit mentions the high prevalence and unmet need for postpartum depression (PPD) treatment in the Medicaid population:

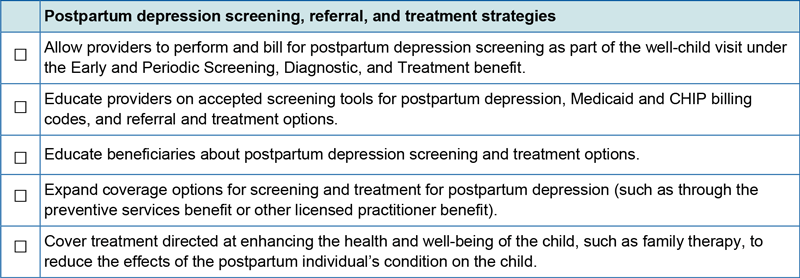

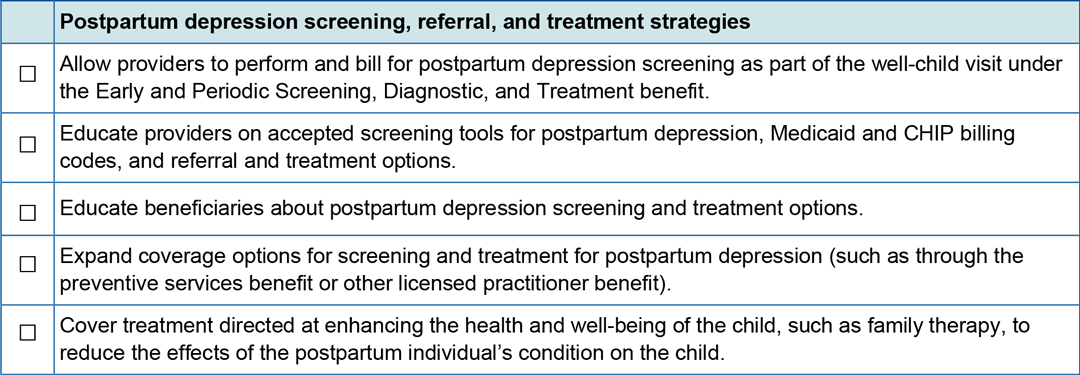

And outlines the postpartum depression screening, referral, and treatment strategies in the following checklists:

Further, Section III: Strategies to Improve the Quality of Postpartum Care, outlines the following:

“The Postpartum depression (PPD) screening, referral, and treatment section emphasizes the high prevalence, severity, and long-term effects of PPD on the mother and child.”

Though the checklist focuses solely on PPD, this section also states, “Providers should also screen for other mental health conditions, such as anxiety and substance use disorder, as these are often co-occurring conditions.”

Our response:

Though CMS only addressed postpartum depression in the checklist, we are pleased CMS addressed other disorders in the body of the toolkit. Anxiety is more prevalent than depression and often a precursor to depression, and women and other birthing people experience a range of disorders and symptoms, including postpartum psychosis which was featured prominently in the news this year.

The toolkit includes the following section:

Postpartum depression screening, referral, and treatment strategies (Pg 20)

The section provides a general overview of postpartum depression and anxiety and also provides direction for Medicaid agencies on how services could be covered:

“PPD screening could be covered as a service under the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit during a well-child visit or claimed under an appropriate state plan benefit for Medicaid-eligible individuals (Box 13). Treatment for PPD could be covered under an array of Medicaid benefits for eligible individuals. Since the PPD depression screening is for the direct benefit of the child, state Medicaid agencies may allow such screenings to be claimed as a service for the child as part of the EPSDT benefit. Diagnostic and treatment services directed solely at the postpartum individual would be coverable under the Medicaid program only if that individual is Medicaid eligible.

However, in some cases, PPD treatment services can be covered as services for a Medicaid-eligible child because they are for the direct benefit of the child (in some cases, these services treat the health and well-being of the child), even if the postpartum individual is not Medicaid eligible. To be claimed as a direct service for the child, PPD treatment must be for the direct benefit of the Medicaid-eligible child and must be delivered to the child and postpartum individual together. As one example, if these conditions are met, states could cover family therapy to reduce the effects of the PPD on the child as a direct service for a Medicaid-eligible child. Several states, including Colorado, Illinois, North Dakota, and Minnesota, cover PPD screening during a Medicaid well-child visit.74 States may instruct providers to claim this activity either as a service for the child or for the postpartum parent, depending on the postpartum parent’s Medicaid eligibility. State Medicaid agencies have flexibility in determining reimbursement approaches for the pediatric provider conducting the PPD screening. See Box 14 for Minnesota’s approach to covering PPD screening during well-child visits and helping providers conduct screening in the pediatric setting. ”

Our Response

We agree that EPSDT can and should cover screening and dyadic mother-infant treatment, however, we are disappointed, as noted above, that CMS failed to mention the critical role of the obstetrician as the mother’s provider in screening and treatment.

In addition to ACOG recommending maternal mental health disorders be addressed by obstetricians, the U.S. Health Resource and Service Administration (HRSA) sanctioned Alliance for Innovation in Maternal Health Care’s (AIM) perinatal mental health recommendation addresses the role of obstetricians in screening for maternal mental health disorders:

“READINESS

Every Unit

Develop workflows for integrating mental health care into preconception and obstetric care before pregnancy through the postpartum period..”

“RECOGNITION & PREVENTION

Every Patient

Screen for perinatal mental health conditions consistently throughout the perinatal period, including but not limited to:

Obtain individual and family mental health history at intake, with review and update as needed. *

Screen for depression and anxiety at the initial prenatal visit, later in pregnancy, and at postpartum visits, ideally including pediatric well-child visits. *

Screen for bipolar disorder before initiating pharmacotherapy for anxiety and depression. *”

Further, it is incredibly unfortunate that CMS missed addressing Medicaid payment to obstetricians for these services, particularly given postpartum Medicaid extension coverage for mothers has been implemented in nearly all 50 states. We have been urging Medicaid agencies to address reimbursement for MMH screening and care given that obstetricians can detect maternal mental health disorders early in pregnancy, and with the proper treatment potential preventing pre-term birth and depression in the postpartum. Obstetricians are generally paid one flat “global maternity” care payment for all care rendered, and therefore payment must be addressed so obstetricians can be made whole for this critical care. The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) also addresses novel ways to incentivize maternal mental healthcare through a pregnancy medical home model and pay-for-performance incentives.

General Observations

The toolkit also provides general recommendations to states:

“Implementing alternative payment methods in Medicaid and CHIP can support several evidence-based options for improving postpartum care, including the use of doulas to engage individuals in their care; the use of care managers or community health workers for more meaningful care coordination.”

Our response:

Doulas are excellent non-clinical professionals to support the delivery of postpartum care, such as breastfeeding, and, with appropriate training and certification, support recovering from maternal mental health disorders.

Certified Peer Support Specialists should also be recognized for their ability to provide support and interventions. Certified peer support specialists are specifically trained to support recovery from mental health disorders. The White House and CMS itself have all called for the use of peers to support mental health workforce expansion, and we are disappointed that CMS missed this opportunity to push state Medicaid agencies to address the powerful role peers can play in providing mental health and substance use support in postpartum care.

All but one state Medicaid agency has state-sanctioned training and certification processes in place, and most reimburse for peer services. However, peer support jobs remain hard to find. Medicaid agencies can play a key role in incentivizing obstetric systems, hospitals, and community-based organizations to create jobs for peers by sharing relevant billing codes and providing technical assistance.

“Providers should either initiate treatment or refer individuals who screen positive for PPD to their primary care provider or other appropriate provider for ongoing support and treatment.”

Our response:

We agree and recognize that referral pathways to mental health are difficult for medical providers to navigate, given mental health carve-outs and behavioral health workforce shortages. We believe that mental health coverage needs to be integrated into medical care insurance contracts so healthcare systems and health clinics can hire and bill for mental health services directly.

In closing

The Policy Center is grateful for CMS’ dedication to improving maternal health outcomes, and applauds their focus on maternal mental health disorders. We look forward to working with CMS to promote screening in obstetric settings and build the workforce, including supporting the employment of certified peer support specialists.